He was odd, Yakov Chernikhov. He drew obsessively. For years. His work was amazing. It still is, 60 years after his death.

He was a rare loner who somehow got stuck between constructivism and Stalinism, who despite his stunning utopian visions, never became an important figure of the Soviet avant-garde.

Chernikhov with students in the early 1920s while still in army service.

He was born in 1889 in a small town in Ukraine, into a poor family of 11 kids. He finished art school in Odessa and then moved to St Petersburg to study at the Academy of Arts. In 1916, mobilised into the army, he worked as a draughtsman. After that he practised as an architect, designing huge industrial buildings for the new Soviet Republic.

In the mid 1920s he founded his own Research Laboratory of Architectural Forms and Methods of Graphic Art. It was an almost unbelievable achievement to have your own studio in those post-revolutionary times. His industrial work had brought him money. He would spend this money publishing his endlessly prolific graphic studies — work he did in parallel to his main architectural practice from the mid 1920s.

Composition no. 16, Architectural Fantasies, 1929-33.

***

Chernikhov was a loner — not part of any of the multitude of avant-garde groups: constructivists, rationalists, etc. He just seemed uninterested in the debates that involved such categories as Marxist, socialist, etc. But he was not oblivious to what was happening around him.

He had upset many people by not acknowledging their theories but allegedly using their discoveries. His peers considered his work amateurish — as well as a vulgar version of earlier formalist trends.

He started from the ornament. This gave rise to 800 drawings executed by him and his pupils. Perhaps he never read Adolf Loos. For him the crime was to carry on regardless without the ornament. Already in this work one can see his obsessiveness: methodical, endless, exhausting compositions.

Then he published Foundations of Contemporary Architecture (1930) and Architecture of Machine Forms (1931): stunning, non-stop variations on vaguely constructivist architectural shapes. He had a rare combination of qualities — a strong artistic temperament and a passion for didacticism and for systems. The graphics are impeccable, the possibilities — limitless.

But then what?

Columbus Monument, Foundations of Contemporary Architecture, 1925-1930

Composition no. 152, Factory-City, Foundations of Contemporary Architecture, 1925-1930.

The text of his books seemed an add-on to the visual work — retrospective rationalisations. They read as didactic, old-fashioned and a little provincial, a naive rehash of rationalist theories. In general, his books had negative reviews.

Then came Architecture Fantasies (1933). This was the most vigorous and powerful manifestation of his talent. Two thousand two hundred and twenty-two (!) graphic sheets at the preliminary exhibition, and in the book. Ten sections — from ornament to landscapes to architectural fantasies. Astounding: the forms, compositions, colours, technique. An inexhaustible multitude of combinations. One loses direction looking at it. Where does he go? What is he trying to achieve? What are the rules?

But then again, who cares?

He was odd, Yakov Chernikhov. He drew obsessively. For years. His work was amazing. It still is, 60 years after his death.

He was a rare loner who somehow got stuck between constructivism and Stalinism, who despite his stunning utopian visions, never became an important figure of the Soviet avant-garde.

Chernikhov with students in the early 1920s while still in army service.

He was born in 1889 in a small town in Ukraine, into a poor family of 11 kids. He finished art school in Odessa and then moved to St Petersburg to study at the Academy of Arts. In 1916, mobilised into the army, he worked as a draughtsman. After that he practised as an architect, designing huge industrial buildings for the new Soviet Republic.

In the mid 1920s he founded his own Research Laboratory of Architectural Forms and Methods of Graphic Art. It was an almost unbelievable achievement to have your own studio in those post-revolutionary times. His industrial work had brought him money. He would spend this money publishing his endlessly prolific graphic studies — work he did in parallel to his main architectural practice from the mid 1920s.

Composition no. 16, Architectural Fantasies, 1929-33.

***

Chernikhov was a loner — not part of any of the multitude of avant-garde groups: constructivists, rationalists, etc. He just seemed uninterested in the debates that involved such categories as Marxist, socialist, etc. But he was not oblivious to what was happening around him.

He had upset many people by not acknowledging their theories but allegedly using their discoveries. His peers considered his work amateurish — as well as a vulgar version of earlier formalist trends.

He started from the ornament. This gave rise to 800 drawings executed by him and his pupils. Perhaps he never read Adolf Loos. For him the crime was to carry on regardless without the ornament. Already in this work one can see his obsessiveness: methodical, endless, exhausting compositions.

Then he published Foundations of Contemporary Architecture (1930) and Architecture of Machine Forms (1931): stunning, non-stop variations on vaguely constructivist architectural shapes. He had a rare combination of qualities — a strong artistic temperament and a passion for didacticism and for systems. The graphics are impeccable, the possibilities — limitless.

But then what?

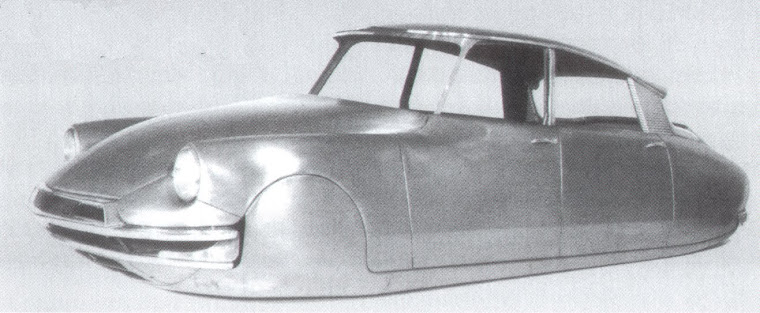

Columbus Monument, Foundations of Contemporary Architecture, 1925-1930

Composition no. 152, Factory-City, Foundations of Contemporary Architecture, 1925-1930.

The text of his books seemed an add-on to the visual work — retrospective rationalisations. They read as didactic, old-fashioned and a little provincial, a naive rehash of rationalist theories. In general, his books had negative reviews.

Then came Architecture Fantasies (1933). This was the most vigorous and powerful manifestation of his talent. Two thousand two hundred and twenty-two (!) graphic sheets at the preliminary exhibition, and in the book. Ten sections — from ornament to landscapes to architectural fantasies. Astounding: the forms, compositions, colours, technique. An inexhaustible multitude of combinations. One loses direction looking at it. Where does he go? What is he trying to achieve? What are the rules?

But then again, who cares?

Composition no. 89, Combination of curved and straight lines with colour illumination, Architectural Fantasies, 1929-1933.

Composition no. 19, Lattice-linear Composition, Architectural Fantasies, 1929-1933.

Even so. is it architecture? There was no brief, no site, no constraint — just a vision. In itself, not so novel — think of Ledoux, Piranesi, Sant'Elia. But the sheer quantity is new: hundreds and hundreds of dazzling sheets, almost of equal strength (making it difficult to make a selection for this blog).

But this enormous quantity of plates, each of which fights for the status of the most original, gave the opposite effect. In the eyes of his contemporaries the quantity degraded the quality. This was not graphic art; it was graphic madness.

Composition no. 21, Complex Spatial Combination of Skyscraper Shapes, Architectural Fantasies, 1929-1933.

Composition no. 16, Illusion, Architectural Fantasies, 1929-1933.

Chernikhov believed that fantasising is useful for any architect. Not at all utopian or romantic, it was practical. Fantasies should be part of an architect's activity. According to him, they showed new compositional processes and new ways of representation. They nurtured a sense of form and colour, trained the imagination, stirred up creative impulses, and lured designers towards new creations and solutions. Forget the limitations, the programme, all the excuses. Be free.

He was also always teaching. But remarkably, never in architectural design, only draughtsmanship.

Composition no. 64, Demonstration of Perspective with Linear Representation, Architectural Fantasies, 1929-1933.

Composition no. 18, Vertical and Horizontal Dynamics, Architectural Fantasies, 1929-1933.

Then came 1935. The wind was changing. The avant-garde, revolution, radicalism — all that was subdued and overwhelmed by a new and vaguely classical agenda. Chernikhov's uncontrollable explosions of incomprehensible energy came to seem dangerous and unwelcome. He was gradually sidelined by his peers, as well as by the authorities. His books were removed from libraries. His laboratory was closed down. His income vanished.

But he continued. He tried to understand what it was they wanted, to see whether his vision could accommodate the new imperatives. He searched for points of fusion and compromise.

So he created the crazy series, Architectural Palaces, Architectural Complexes and Palaces of Communism (1934-1941). One can see the progression, but there is also a break with his earlier work.

These could be palaces of anything — monstrous Babylonian hallucinations, huge sci-fi complexes, totalitarian labyrinths or Piranesian/Stalinist prisons. They possess an excruciating symmetry and potential for enormous processions.

Where are these palaces? What are they for? There was no text accompanying the designs. Because, since they were not published, no explanation was needed.

It is so ironic, sad and telling. Chernikhov always advocated the abstract — abstract from programme, from politics, from trends, from fashion. And then, it appeared to be impossible. He was so much of his time. Whatever he did, he was the hostage and prisoner of his time; prisoner of the prisons he drew.

Composition from series Palaces of Communism, 1934-41

These designs are inhuman in scale as well as in their virtuosic execution. There are never any people in these visions. Gigantic, monumental, scary and mesmerising, they are staged in an empty city.

But you wonder, since they were so much of their Stalinist epoch, why the authorities censored them. Too gothic, too constructivist, too much emotion perhaps?

But looking at them today, they are still very modern: pure vision, pure image. His creations look like the results of a genuine programme, and like real solutions. Perhaps because, as he thought, one can't really draw a meaningless or absurd image. The image has its logic. And compositional logic equates to that of a real commission.

Composition from the series Palaces of Communism, 1934-41.

After that phase, came Architectural Fairy Tales and Architectural Romances. It was all getting more and more amorphous and further away from architecture. The lines became more vague, spaces blurred, outlines became weak, and colours mute.

Then came a pathetic letter to Stalin asking for permission to publish. (No answer: no hope).

Architectural Romances, early 1940s

When the war started in 1941, Chernikhov was drafted into making huge camouflage canvases to be spread above Moscow to confuse enemy pilots. From a speeding plane, the city centre would look like woods or fields of crops. Nowadays art critics call the studies for these huge canvases abstract paintings. In fact, they were perhaps the most functional images he ever made.

Abstract painting for military camouflage, early 1940s

In July 1942, three years before victory, Chernikhov started the series Pantheons of the Great Patriotic War — designs for monuments to the future victory and future dead. Again, it seems that creation was a therapy for him — in the fever of designing, nothing bad can happen, no fear can overwhelm you.

Composition from Pantheons of the Great Patriotic War

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario